The Juneteenth holiday does not come up in a search of the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America database, scoped to Connecticut newspapers before 1963.

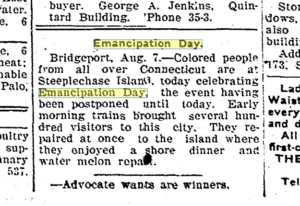

However, historically it appears that communities in Connecticut did celebrate, but referred to the celebrations to mark the abolition of slavery resulting from the Union military victory in the Civil War as “Emancipation Day.” It appears that the “Emancipation Day” was sometimes observed in January, April, June or August.

Below are a sampling of the oldest Connecticut clippings found regarding the observance of the holiday. Please be advised that the language and attitude of the articles is frequently racist.

More importantly, however, these clippings document the persistence of the holiday, which remained part of the nation’s patriotic celebrations, despite being ignored or denigrated by the White press over the past 159 years.

The Hartford Courant, August 3, 1865 – an August celebration in Brooklyn, NY, 4 months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, VA.

Litchfield Enquirer, January 4, 1872 – January celebration in New Haven

July 19th, 1872 – Willimantic Journal

August 8, 1873, the Connecticut Western News decided to be particularly racist in referring to the celebration.

August 7, 1874, the Willimantic Journal reports on Frederick Douglass’ presence at the Bridgeport celebration.

August 8, 1880, Morning Journal Courier reported on the celebration at Elmira, NY.

Aug 2, 1881, Morning Journal Courier again…

April 28, 1882. The Willimantic Journal placed the celebration in Washington, D.C. in April, and with a racist flourish.

August 1, 1894, Stamford Daily Advocate – Frederick Douglass in attendance at Brooklyn celebration.

August 27, 1908, Stamford Daily Advocate – twenty days after the fact.

July 7, 1925, the New Britain Herald, 99 years ago, mentions “Emancipation Day” in Oklahoma as being celebrated on June 19th. In the story, a Black man was sentenced to die on the Juneteenth holiday, but the Sheriff who was to carry out the execution forgot, and arrangements had to be made to execute the prisoner at a later date.

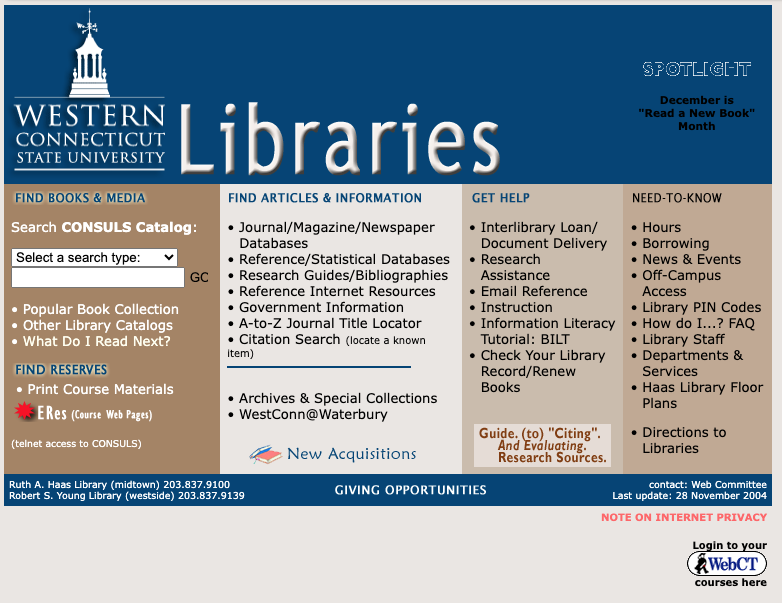

Newspaper and archival collections provide a means to explore topics such as this.

In 1863, as the Civil War was about to enter its final full year, the Hartford Courant wrote on Thanksgiving day which in 1863 occurred today. It might give some insight on how the holiday was perceived at that time. See the WCSU Library’s databases to see more from the Hartford Courant.

In 1863, as the Civil War was about to enter its final full year, the Hartford Courant wrote on Thanksgiving day which in 1863 occurred today. It might give some insight on how the holiday was perceived at that time. See the WCSU Library’s databases to see more from the Hartford Courant.